Untitled Document

Student loans, for more than half those attending college, are the

new paradigm of college funding. Consequently, student debt is, or will soon

be, the new paradigm of early to middle adult life. Gone are the days when the

state university was as cheap as a laptop and was considered a right, like secondary

education. Now higher education is, like most social services, a largely privatized

venture, and loans are the chief way that a majority of individuals pay for

it.

Over the past decade, there has been an avalanche of criticism of the “corporatization”

of the university. Most of it focuses on the impact of corporate protocols on

research, the reconfiguration of the relative power of administration and faculty,

and the transformation of academic into casual labor, but little of it has addressed

student debt. Because more than half the students attending university receive,

along with their bachelor’s degree, a sizable loan payment book, we need

to deal with student debt.

The average undergraduate student loan debt in 2002 was $18,900. It more than

doubled from 1992, when it was $9,200. Added to this is charge card debt, which

averaged $3,000 in 2002, boosting the average total debt to about $22,000. One

can reasonably expect, given still accelerating costs, that it is over $30,000

now. Bear in mind that this does not include other private loans or the debt

that parents take on to send their children to college. (Neither does it account

for “post-baccalaureate loans,” which more than doubled in seven

years, from $18,572 in 1992–1993 to $38,428 in 1999–2000, and have

likely doubled again).

Federal student loans are a relatively new invention. The Guaranteed Student

Loan (GSL) program only began in 1965, a branch of Lyndon B. Johnson’s

Great Society programs intended to provide supplemental aid to students who

otherwise could not attend college or would have to work excessively while in

school. In its first dozen years, the amounts borrowed were relatively small,

in large part because a college education was comparatively inexpensive, especially

at public universities. From 1965 to 1978, the program was a modest one, issuing

about $12 billion in total, or less than $1 billion a year. By the early 1990s,

the program grew immodestly, jumping to $15 billion to $20 billion a year, and

now it is over $50 billion a year, accounting for 59 percent of higher educational

aid that the federal government provides, surpassing all grants and scholarships.

The reason that debt has increased so much and so quickly is that tuition and

fees have increased, at roughly three times the rate of inflation. Tuition and

fees have gone up from an average of $924 in 1976, when I first went to college,

to $6,067 in 2002. The average encompasses all institutions, from community

colleges to Ivies. At private universities, the average jumped from $3,051 to

$22,686. In 1976, the tuition and fees at Ivies were about $4,000; now they

are near $33,000. The more salient figure of tuition, fees, room, and board

(though not including other expenses, such as books or travel to and from home)

has gone up from an average of $2,275 in 1976, $3,101 in 1980, and $6,562 in

1990, to $12,111 in 2002. At the same rate, gasoline would now be about $6 a

gallon and movies $30.

This increase has put a disproportionate burden on students and their families—hence

loans. The median household income for a family of four was about $24,300 in

1980, $41,400 in 1990, and $54,200 in 2000. In addition to the debt that students

take on, there are few statistics on how much parents pay and how they pay it.

It has become common for parents to finance college through home equity loans

and home refinancing. Although it is difficult to measure these costs separately,

paying for college no doubt forms part of the accelerating indebtedness of average

American families.

Students used to say, “I’m working my way through college.”

Now it would be impossible to do that unless you have superhuman powers. According

to one set of statistics, during the 1960s, a student could work fifteen hours

a week at minimum wage during the school term and forty in the summer and pay

his or her public university education; at an Ivy or similar private school,

the figure would have been about twenty hours a week during term. Now, one would

have to work fifty-two hours a week all year long; at an Ivy League college,

you would have to work 136 hours a week all year. Thus the need for loans as

a supplement, even if a student is working and parents have saved.

The reason tuition has increased so precipitously is more complicated. Sometimes

politicians blame it on the inefficiency of academe, but most universities,

especially state universities, have undergone retrenchment if not austerity

measures for the past twenty years. Tuition has increased in large part because

there is significantly less federal funding to states for education, and the

states fund a far smaller percentage of tuition costs. In 1980, states funded

nearly half of tuition costs; by 2000, they contributed only 32 percent. Universities

have turned to a number of alternative sources to replace the lost funds, such

as “technology transfers” and other “partnerships” with

business and seemingly endless campaigns for donations; but the steadiest way,

one replenished each fall like the harvest, is through tuition.

ALTHOUGH state legislators might flatter themselves on their

belt-tightening, this is a shell game that slides the cost elsewhere—from

the public tax roll to individual students and their parents. This represents

a shift in the idea of higher education from a public entitlement to a private

service. The post–World War II idea, forged by people like James Bryant

Conant, the president of Harvard and a major policy maker, held that the university

should be a meritocratic institution, not just to provide opportunity to its

students but to take advantage of the best and the brightest to build America.

To that end, the designers of the postwar university kept tuitions low, opening

the gates to record numbers of students, particularly from classes previously

excluded. I have called this “the welfare state university” because

it instantiated the policies and ethos of the postwar, liberal welfare state.

Now the paradigm for university funding is no longer a public entitlement primarily

offset by the state but a privatized service: citizens have to pay a substantial

portion of their own way. I call this the “post–welfare state university,”

because it carries out the policies and ethos of the neoconservative dismantling

of the welfare state, from the “Reagan Revolution” through the Clinton

“reform” up to the present draining of social services. The principle

is that citizens should pay more directly for public services, and public services

should be administered less through the state and more through private enterprise.

The state’s role is not to provide an alternative realm apart from the

market but to grease the wheels of the market, subsidizing citizens to participate

in it and businesses to provide social services. Loans carry out the logic of

the post–welfare state because they reconfigure college funding not as

an entitlement or grant but as self-payment (as with welfare, fostering “personal

responsibility”), and not as a state service but a privatized service,

administered by megabanks such as Citibank, as well as Sallie Mae and Nellie

Mae, the original federal nonprofit lenders, although they have recently become

independent for-profits. The state encourages participation in the market of

higher education by subsidizing interest, like a start-up business loan, but

eschews dependence, as it leaves the principal to each citizen. You have to

pull yourself up by your own bootstraps.

This also represents a shift in the idea of higher education from a social

to an individual good. In the postwar years, higher education was conceived

as a massive national mobilization, in part as a carryover from the war ethos,

in part as a legacy of the New Deal, and in part as a response to the cold war.

It adopted a modified socialism, like a vaccine assimilating a weaker strain

of communism in order to immunize against it. Although there was a liberal belief

in the sanctity of the individual, the unifying aim was the social good: to

produce the engineers, scientists, and even humanists who would strengthen the

country. Now higher education is conceived almost entirely as a good for individuals:

to get a better job and higher lifetime earnings. Those who attend university

are construed as atomized individuals making a personal choice in the marketplace

of education to maximize their economic potential. This is presumably a good

for the social whole, all the atoms adding up to a more prosperous economy,

but it is based on the conception of society as a market driven by individual

competition rather than social cooperation, and it defines the social good as

that which fosters a profitable market. Loans are a personal investment in one’s

market potential rather than a public investment in one’s social potential.

Like a business, each individual is a store of human capital, and higher education

provides value-added.

THIS REPRESENTS another shift in the idea of higher education,

from youthful exemption to market conscription, which is also a shift in our

vision of the future and particularly in the hopes we share for our young. The

traditional idea of education is based on social hope, providing an exemption

from work and expense for the younger members of society so that they can explore

their interests, develop their talents, and receive useful training, as well

as become versed in citizenship—all this in the belief that society will

benefit in the future. Society pays it forward. This obviously applies to elementary

and secondary education (although given the voucher movement, it is no longer

assured there, either), and it was extended to the university, particularly

in the industrial era. The reasoning melds citizenship ideals and utilitarian

purpose. The classical idea of the American university propounded by Thomas

Jefferson holds that democratic participation requires education in democratic

principles, so it is an obligation of a democracy to provide that education.

(The argument relates to the concept of franchise: just as you should not have

to pay a poll tax to vote, you should not have to pay to become a properly educated

citizen capable of participating in democracy.) The utilitarian idea, propounded

by Charles Eliot Norton in the late nineteenth century and James Conant in the

mid-twentieth, holds that society should provide the advanced training necessary

in an industrially and technologically sophisticated world. The welfare state

university promulgated both ideal and utilitarian goals, providing inexpensive

tuition and generous aid while undergoing a massive expansion of physical campuses.

It offered its exemption not to abet the leisure of a new aristocracy (Conant’s

aim was to dislodge the entrenched aristocracy of Harvard); it presupposed the

long-term social benefit of such an exemption, and indeed the GI Bill earned

a return of seven to one for every dollar invested, a rate that would make any

stockbroker turn green. It also aimed to create a strong civic culture. The

new funding paradigm, by contrast, views the young not as a special group to

be exempted or protected from the market but as fair game in the market. It

extracts more work—like workfare instead of welfare—from students,

both in the hours they clock while in school as well as in the deferred work

entailed by their loans. Debt puts a sizable tariff on social hope.

Loans to provide emergency or supplemental aid are not necessarily a bad arrangement.

But as a major and mandatory source of current funding (most colleges, in their

financial aid calculations, stipulate a sizable portion in loans), they are

excessive if not draconian. Moreover, as currently instituted, they are more

an entitlement for bankers than for students. The way they work for students

is that the federal government pays the interest while the student is enrolled

in college and for a short grace period after graduation, providing a modest

“start-up” subsidy, as with a business loan, but no aid toward the

actual principal or “investment.” For lenders, the federal government

insures the loans. In other words, banks bear no risk; federal loan programs

provide a safety net for banks, not for students. Even by the standards of the

most doctrinaire market believer, this is bad capitalism. The premise of money

lending and investment, say for a home mortgage, is that interest is assessed

and earned in proportion to risk. As a result of these policies, the banks have

profited stunningly. Sallie Mae, the largest lender, returned the phenomenal

profit rate of 37 percent in 2004. Something is wrong with this picture.

There is no similar safety net for students. Even if a person is in bankruptcy

and absolved of all credit card and other loans, the one debt that cannot be

forgone is student loans. This has created what the journalists David Lipsky

and Alexander Abrams have called a generation of “indentured students.”

We will not know the full effects of this system for at least twenty years,

although one can reasonably predict it will not have the salutary effects that

the GI Bill had. Or, simply, students from less privileged classes will not

go to college. According to current statistics, the bottom quarter of the wealthiest

class of students is more likely to go to college than the top quarter of the

least wealthy students. Opportunity for higher education is not equal.

DEBT IS NOT just a mode of financing but a mode of pedagogy.

We tend to think of it as a necessary evil attached to higher education but

extraneous to the aims of higher education. What if we were to see it as central

to people’s actual experience of college? What do we teach students when

we usher them into the post–welfare state university?

There are a host of standard, if sometimes contradictory, rationales for higher

education. On the more idealistic end of the spectrum, the traditional rationale

is that we give students a broad grounding in humanistic knowledge—in

the Arnoldian credo, “the best that has been known and thought.”

A corollary is that they explore liberally across the band of disciplines (hence

“liberal education” in a nonpolitical sense). A related rationale

is that the university is a place where students can conduct self-exploration;

although this sometimes seems to abet the “me culture” or “culture

of narcissism” as opposed to the more stern idea of accumulating knowledge,

it actually has its roots in Socrates’s dictum to know oneself, and in

many ways it was Cardinal John Henry Newman’s primary aim in The Idea

of a University. These rationales hold the university apart from the normal

transactions of the world.

In the middle of the spectrum, another traditional rationale holds that higher

education promotes a national culture; we teach the profundity of American or,

more generally, Western, culture. A more progressive rationale might reject

the nationalism of that aim and posit instead that higher education should teach

a more expansive and inclusive world culture but still maintain the principle

of liberal learning. Both rationales maintain an idealistic strain—educating

citizens—but see the university as attached to the world rather than as

a refuge from it. At the most worldly end of the spectrum, a common rationale

holds that higher education provides professional skills and training. Although

this utilitarian purpose opposes Newman’s classic idea, it shares the

fundamental premise that higher education exists to provide students with an

exemption from the world of work and a head start before entering adult life.

Almost every college and university in the United States announces these goals

in its mission statement, stitching together idealistic, civic, and utilitarian

purposes in a sometimes clashing but conjoined quilt.

The lessons of debt diverge from these traditional rationales. First, debt

teaches that higher education is a consumer service. It is a pay-as-you-go transaction,

like any other consumer enterprise, subject to the business franchises attached

to education. All the entities making up the present university multiplex reinforce

this lesson, from the Starbucks kiosk in the library and the Burger King counter

in the dining hall, to the Barnes & Noble bookstore and the pseudo–Golds

Gym rec center—as well as the banking kiosk (with the easy access Web

page) so that they can pay for it all. We might tell students that the foremost

purpose of higher education is self-searching or liberal learning, but their

experience tells them differently.

Second, debt teaches career choices. It teaches that it would be a poor choice

to wait on tables while writing a novel or become an elementary school teacher

at $24,000 or join the Peace Corps. It rules out culture industries such as

publishing or theater or art galleries that pay notoriously little or nonprofits

like community radio or a women’s shelter. The more rational choice is

to work for a big corporation or go to law school. Nellie Mae, one of the major

lenders, discounted the effect of loans on such choices, reporting that “Only

17 percent of borrowers said student loans had a significant impact on their

career plans.” It concluded, “The effect of student loans on career

plans remains small.” This is a dubious conclusion, as 17 percent on any

statistical survey is not negligible. The survey is flawed because it assessed

students’ responses at graduation, before they actually had to get jobs

and pay the loans, or simply when they saw things optimistically. Finally, it

is fundamentally skewed because it assumes that students decide on career plans

tabula rasa. Most likely, many students have already recognized the situation

they face and adapted their career plans accordingly. The best evidence for

this is the warp in majors toward business. Many bemoan the fact that the liberal

arts have faded as undergraduate majors, while business majors have nearly tripled,

from about 8 percent before the Second World War to 22 percent now. This is

not because students no longer care about poetry or philosophy. Rather, they

have learned the lesson of the world in front of them and chosen according to

its, and their, constraints.

Third, debt teaches a worldview. Following up on the way that advertising indoctrinates

children into the market, as Juliet Schor shows in Born to Buy, student loans

directly conscript college students. Debt teaches that the primary ordering

principle of the world is the capitalist market, and that the market is natural,

inevitable, and implacable. There is no realm of human life anterior to the

market; ideas, knowledge, and even sex (which is a significant part of the social

education of college students) simply form sub-markets. Debt teaches that democracy

is a market; freedom is the ability to make choices from all the shelves. And

the market is a good: it promotes better products through competition rather

than aimless leisure; and it is fair because, like a casino, the rules are clear,

and anyone—black, green, or white—can lay down chips. It is unfortunate

if you don’t have many chips to lay down, but the house will spot you

some, and having chips is a matter of the luck of the social draw. There is

a certain impermeability to the idea of the market: you can fault social arrangements,

but whom do you fault for luck?

Fourth, debt teaches civic lessons. It teaches that the state’s role

is to augment commerce, abetting consuming, which spurs producing; its role

is not to interfere with the market, except to catalyze it. Debt teaches that

the social contract is an obligation to the institutions of capital, which in

turn give you all of the products on the shelves. It also teaches the relation

of public and private. Each citizen is a private subscriber to public services

and should pay his or her own way; social entitlements such as welfare promote

laziness rather than the proper competitive spirit. Debt is the civic version

of tough love.

Fifth, debt teaches the worth of a person. Worth is measured not according

to a humanistic conception of character, cultivation of intellect and taste,

or knowledge of the liberal arts, but according to one’s financial potential.

Education provides value-added to the individual so serviced, in a simple equation:

you are how much you can make, minus how much you owe. Debt teaches that the

disparities of wealth are an issue of the individual, rather than society; debt

is your free choice.

Last, debt teaches a specific sensibility. It inculcates what Barbara Ehrenreich

calls “the fear of falling,” which she defines as the quintessential

attitude of members of the professional middle class who attain their standing

through educational credentials rather than wealth. It inducts students into

the realm of stress, worry, and pressure, reinforced with each monthly payment

for the next fifteen years.

IF YOU BELIEVE in the social hope of the young, the present

system of student debt is wrong. And if you look at the productivity statistics

of the college-educated World War II generation, it is counterproductive. We

should therefore advocate the abolition of student debt. Despite Nellie Mae’s

bruiting the high rate of satisfaction, a number of universities, including

Princeton and UNC-Chapel Hill, have recognized the untenable prospect of student

debt and now stipulate aid without loans. This is a step in the right direction.

It should be the official policy of every university to forgo loans, except

on an emergency basis. And it should be the policy of the federal government

to convert all loan funds—more than $50 billion!—to direct aid,

such as Pell Grants.

Even if this can only be enacted in the long term, a short-term solution should

be to retain the basic structure of student loans but to shift to direct lending

administered from the federal government to colleges (which university administrators

preferred, but bank lobbies overrode several years ago) or to regulate and reduce

the interest rates. If banks still process loans, the loans are funded by the

federal government, and the banks take no risk, then they should only receive

a 1 percent or 2 percent administrative surcharge, such as charge card companies

extract from businesses when processing a payment. If Sallie Mae makes a 37

percent profit on a public service, then it is no better than war profiteers

who drain money from public coffers for a necessary service, and it should pay

it back. Or there should be a national, nonprofit education foundation that

operates at margin and administers the loans without profit.

A MORE far-ranging solution is free tuition. Adolph Reed,

as part of a campaign of the Labor Party for “Free Higher Ed,” has

made the seemingly utopian but actually practical proposal of free tuition for

all qualified college students. If education is a social good, he reasons, then

we should support it; it produced great benefits, financial as well as civic,

under the GI Bill (see his “A GI Bill for Everyone,” Dissent, Fall

2001); and, given current spending on loan programs, it is not out of reach.

He estimates that free tuition at public institutions would cost $30 billion

to $50 billion a year, only a small portion of the military budget. In fact,

it would save money by cutting out the middle stratum of banking. The brilliance

of this proposal is that it applies to anyone, rich or poor, so that it realizes

the principle of equal opportunity but avoids “class warfare.”

Another idea that I have proposed is for programs oriented toward loan abatements

or forgiveness. These would help those in Generations X or Y who are already

under the weight of debt. My proposal takes a few pages from European models

of national service, programs such as AmeriCorps (but expanded and better funded),

and throwbacks such as the Works Progress Administration. Such a proposal would

also require federal funding, though it could be administered on the state or

federal level. It would call for a set term of, say, two or three years of service

in exchange for a fair if modest salary and forgiveness of a significant portion

of education loans per year in service.

Several existing programs could be expanded. One is a very successful undergraduate

program—the North Carolina Teaching Fellows Program—which carries

a generous scholarship as well as other “enrichments” designed to

recruit some of the better but usually less wealthy high school students into

teaching. It requires that students teach in less privileged school districts,

often rural or sometimes inner city, for a term of three or four years after

graduation. On the postgraduate level, there are similar programs designed to

bring doctors to rural or impoverished areas that lack them by subsidizing medical

school training in exchange for a term of service. This program could extend

to the Ph.D. level, helping to remedy graduate indebtedness as well as the academic

job crisis in which there are too few decent jobs for graduates. A Ph.D. in

literature or history, for instance, could be sent to community colleges or

high schools to consult on programs and teach upgrade courses for veteran teachers

on recent developments in scholarship or special courses to students. We should

build a system of National Teaching Fellows who would teach and consult in areas

where access to higher education has been limited.

Such a program would have obvious benefits for students, giving them a way

to shed the draconian weight of debt, as well as giving them experience beyond

school and, more intangibly, a sense of pride in public service. As a side effect,

it would likely foster a sense of solidarity, as the national service of the

World War II generation did for soldiers from varied walks of life, or as required

national service does in some European countries. The program would put academic

expertise to a wider public use, reaching those in remote or impoverished areas.

As a side effect, it would foster a better image of academe, through face-to-face

contact. Just as law-and-order political candidates promise more police on the

streets, we should be pressuring political candidates for more teachers in our

classrooms and thus smaller class sizes, from preschool to university.

These proposals might seem far-fetched, but a few short years before they were

enacted, programs like the Works Progress Administration, Social Security, the

GI Bill, or the Peace Corps, also seemed far-fetched. There is a maxim, attributed

to Dostoyevsky, that you can judge the state of a civilization from its prisons.

You can also judge the state of a civilization from its schools—or, more

generally, from how it treats its young as they enter the full franchise of

adult life. Encumbering our young with mortgages on their futures augurs a return

of debtors’ prisons. Student debt impedes a full franchise in American

life, so we must begin the debate about how to restore the democratic promise

of education.

Jeffrey J. Williams’s most recent book is Critics

at Work: Interviews 1992-2003 (New York University Press, 2004). He teaches

at Carnegie Mellon University.

_______________________

Lack of college aid stifles ambition

DAVE NEWBART

Chicago

Sun-Times

Needy students at Illinois' public universities are straddling the biggest

gap ever between skyrocketing tuition bills and stagnant pools of financial

aid. Now more than $200 million short of funds to meet financial need, Illinois

public universities must count on students to pay a far larger portion of the

tuition bills.

In the last five years, the amount of unmet need at Illinois universities rose

nearly 50 percent.

That has forced some students to take out more loans or work longer hours to

pay for school -- on top of loans and work study they already shouldered under

federal financial aid formulas. Others have dropped courses or live at home

to save money. Still others switch to more affordable two-year community colleges.

DEFINING 'UNMET NEED'

Based on family income, assets and savings, the federal government determines

a student's Expected Family Contribution -- or the amount of money a student's

family can afford to pay toward college. The difference between your that

amount and the total cost to attend a school (including tuition and fees,

books, living, transportation and other expenses) is the amount of financial

need you have. Schools package federal, state and institutional grants along

with federally backed student loans and work-study to meet that need. The

amount of need that the school still can't meet is considered unmet need.

RELATED CHART

How much the gap between costs and available financial aid has increased

overall, and for the average recipient, at public Illinois universities.

Click

here to view the chart »

|

|

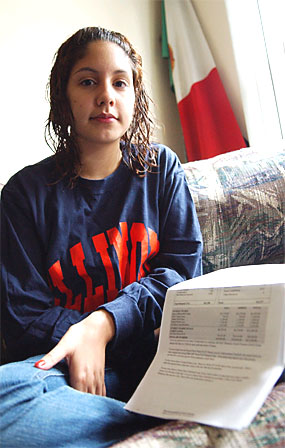

Dora Magallon of the Austin neighborhood was accepted by the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign but won't be going because her aid package had too many loans and still fell $3,000 short. (JEAN LACHAT/ SUN-TIMES)

|

Dora Magallon was accepted by the state's flagship public school, the University

of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign -- but won't go because her aid package had

too many loans and was nearly $3,000 short of what she needed. She is now planning

to attend Triton College this fall.

"Just working so hard to go there and then having to end up at a community

college is disappointing,'' said Magallon, 18, of the Far West Side.

'It's discouraging'

Mary Guzman, 25, of Bensenville, took a full-time job, moved in with an uncle

and dropped classes to be able to afford education courses at Chicago State

University. Her aid packages at the school the last two years were a combined

$21,130 short of her estimated need.

"It's discouraging,'' said Guzman, who is supporting herself. "I

just want to say forget it.''

For students with unmet need, the average gap in aid at each school now ranges

from $1,700 to nearly $7,000 per student, according to a Chicago Sun-Times survey

of the 11 public, four-year universities in the state. The gap at all of the

schools surveyed exceeded the $1,400 average at public universities nationwide,

according to Postsecondary Education Opportunity, a newsletter that analyzes

higher-education trends.

While many students do receive enough aid to meet their need, experts said

the reason for the growing gap for others boils down to two main factors: stagnant

federal and state aid and rapidly rising tuition. Federal Pell grants have increased

only $50, to $4,050, since 2002. The maximum grant awarded under the Illinois

Monetary Award Program went down 10 percent in the last five years, to $4,520.

Things will improve this fall as MAP grants increase to nearly $4,870. The

Illinois Student Assistance Commission will consider increasing that by an additional

$100 at a special meeting Wednesday. Gov. Blagojevich on Sunday signed a bill

creating a new MAP Plus program that offers $500 scholarships to students who

maintain good grades and come from families with income under $200,000.

'They go into a panic'

And a new federal program will grant more money to Pell-eligible students who

take rigorous high school curriculums or major in high-demand areas like science,

math and technology.

Meanwhile, tuition has gone up between 70 percent and 115 percent for new students

at those schools since 2001-2002.

Those realities have made the college admission process a mixed bag for students,

said Ivette Nieves, director of Aspira, a youth development center in Logan

Square that helps students in the financial aid process.

"When they receive the letter of acceptance, it's good news,'' she said.

"When they receive the financial aid letter, they go into a panic.''

Guzman said she plans to stick with it at CSU, possibly by taking even more

loans.

CSU officials said the high level of unmet need at their school -- nearly $7,000

per student, on average -- reflects the fact that a majority of its students

are low-income. The school is about to launch a major fund-raising campaign

that in part will go to address unmet need.

Middle-class families also get hit hard, experts said. In recognition of that

problem, state Sen. Miguel Del Valle (D- Chicago) only awards full- tuition

General Assembly scholarships to students who aren't eligible for Pell or MAP

grants.

$7,000 shortfall

Eighteen-year-old Melanie Flores learned last week that she had been granted

a one-year full-tuition scholarship to the U. of I. by Del Valle. Until then,

she had been scrambling to figure out how to afford $21,298 to attend school

Downstate for one year. That figure includes tuition, fees, books, transportation

and other expenses.

|

|

Melanie Flores will be attending the U. of I. on a full-tuition scholarship arranged by state Sen. Miguel Del Valle. (KEITH HALE/SUN-TIMES)

|

Her parents' combined income is $65,000. When she submitted her financial aid

application to the federal government, it determined her family could afford

$11,715 of the total bill. But she did not qualify for any federal or state

grants, and the U. of I. didn't offer her any institutional awards. She was

offered a $2,625 student loan.

That means she had nearly $7,000 in unmet need -- until Del Valle stepped in

-- on top of her family contribution. While the U. of I. offered her parents

an $18,000 loan, financial aid administrators acknowledge such a loan really

doesn't meet student need.

She was elated to receive the scholarship, but she is still trying to find

help to pay her other costs beyond tuition.

'Every year, it's getting worse'

"I don't want to be one of those students having to pay so much when I

graduate,'' said Flores, who ranked 14th in her class at Noble Street Charter

High School in Chicago.

Officials at the U. of I. say since the late 1990s, it has become harder to

completely fill every student's need. For the last several years, the school

has spent millions in institutional funds (including $9 million last year) to

fill the growing gap between the maximum MAP grant and tuition. Low-cost federal

student loans have also been restricted even as tuition went up.

And middle-class students have problems because needier students tend to get

more of the available grant money.

"Every year, it's getting worse,'' said Bob Andersen, senior associate

director of financial aid at the U. of I. "At first, a lot of parents can

ask grandma and grandpa and uncle and aunt to help make up the difference. But

unless something is done, it's going to get really bad.''

The U. of I. offered Magallon a grant of nearly $1,500. She was eligible for

a partial MAP grant and work study. They also offered her two loans totaling

more than $6,000 for her first year next fall.

"My parents said that's too much of a debt to take on at such a young

age,'' Magallon said . Instead of moving into the dorms with other students

she knows attending the school, she'll live at home while attending Triton.

"It's disappointing. I don't know how they expect me to come up with all

this money. U. of I. was my top choice.''